|

Director Peter Jackson might have felt a bit

Frodo-ish when he got the job of bringing Tolkien's trilogy to the screen. He

has made most of his quirky little films (the deranged puppet farce Meet the

Feebles, the zombie classic Braindead, the rapturous murder story Heavenly

Creatures) in his native New Zealand. True to form, he shot this three-part,

$300 million fantasy back home — and back-to-back-to-back. Shooting is

completed on all three films, which will be released in consecutive Decembers,

beginning with this month's The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring.

Now he has to be ready for all sorts of comparisons: not just with the Tolkien

originals, but with a certain other fantasy film franchise launched this year.

If Jackson ever fretted, he needn't have. Like

Frodo, he should emerge triumphant, for The Fellowship of the Ring is a bigger,

richer, way-better film than Harry Potter and the Philosopher's (or Sorcerer's,

depending on where you live) Stone. Jackson's work is not simply a sumptuous

illustration of a favorite fable; though faithful in every detail to Tolkien,

it has a vigorous life of its own. And it possesses a grandeur, a moral heft

and emotional depth, that the Potter people never tried for.

Part of the difference between the films and

their relative achievements derives from the source novels. Rowling's work is

an intimate epic, a Tom Brown's School Days with some fabulous sleight-of-hand,

and featuring a trim trio of central characters: the Magical Musketeers of

English adolescence. Tolkien's is an Iliad, a vast tale of war, sprawling

across Middle Earth in a metaphor for the Allies' battle against Hitler (in the

book, the Dark Lord Sauron) or, for that matter, the U.S. and the Northern

Alliance against Osama bin Laden and the Taliban. Its cast of characters is

huge, varied (humans, dwarves, elves, wraiths, Orcs, Ents) and adult.

The only childlike creatures are the Hobbits,

short of stature and averse to responsibility. In this sense, Frodo and his

pals Pippin and Sam, whose maturity is won in bitter trials, have echoes in

Harry and his chums Hermione and Ron. But the Hobbits' journey has heartache at

its core: they are like kids drafted into a holy, hellish war. And Frodo, as

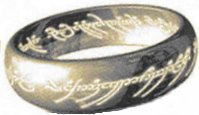

the Ring bearer, has what amounts to a suicide mission: the Ring both empowers

and corrupts anyone who would have it.

So any apt adaptation of Lord of the Rings is

bound to have a gravity, even a kind of dread, about the awful task at hand.

Jackson's film has that gravity. But it is also a buoyant experience — an

excellent film and a ripping yarn of a movie — because the characters are

lively and engaging, and because the production team put such skill and joy

into designing a movie Middle Earth. The landscapes, a cunning mixture of

computer images and real New Zealand, bestow a distinct and beguiling

personality to each realm: the elves' sylvan fairy land, the dwarves' dark

Mines of Moria, the fabulous castle of chief wizard Saruman and, of course, the

Hobbits' own Shire.

Think of the River Bank from The Wind in the

Willows, but on the grandest scale, with dozens of Hobbit homes built into

hillsides. The hutches have a sturdiness — part medieval, part Art Nouveau

— that takes its style cues from the natural environment; lots of solid

furniture, and hardly a right angle in sight. The Hobbits blend in, too. They

are short, round-faced, curly-haired and hairy-footed, and the movie perfectly

visualizes them. One of the film's small miracles is the persuasive integration

of these 1.1-m-tall creatures into scenes with all the bigger people. It's done

with forced perspective, back projection, clever intercutting and frequent

doubling of the standard-size actors by small folks seen from behind.

It's said that, in movies, 90% of good acting

is good casting. Every time a new actor shows up — Viggo Mortensen as

Prince Aragon, Sean Bean as gruff, troubled Boromir, Cate Blanchett and Liv

Tyler as two great ladies of the wood and lake — the viewer says, "Yes,

he/she is just right." As Frodo, Elijah Wood uses his giant eyes to project a

kind of haunted innocence. And Ian McKellen has a lovely time as the wizard

Gandalf; he sparkles with wisdom, humor, sympathy and worry. Together they

paint a living portrait of Middle Earth's many peoples and conflicting agendas.

A few caveats for parents: the film is never

gross, but it's sometimes scary. At 2 hr. 58 min., it will test children's

endurance and their bladders — but probably not their patience. (Besides,

an informal poll of New Yorkers who'd seen the 2 hr. 32 min. Harry Potter film

indicated that adults thought it slow and stodgy while the kids complained that

it wasn't long enough.) Fellowship may disappoint children because it lacks a

conventionally satisfying resolution; the movie ends, as the first book does,

on the cusp of a great adventure. Like Oliver Twist in the Workhouse, kids may

be wailing, "Please, sir, I want some more" for the next 12 months.

But that is the seductive tease of great

bedtime stories. Jackson's achievement is nearly at that level. His movie

achieves what the best fairy tales do: the creation of an alternate world,

plausible and persuasive, where the young — and not only the young —

can lose themselves. And perhaps, in identifying with the little Hobbit that

could, find their better selves.

Richard Corliss

Time, 19.12. 2001 |