|

|

Only one of Maxim Gorky's many plays is at all well known in this country - The Lower Depths, one of the great masterpieces of the naturalistic theatre. But after the success of that intricately structured picture of Russian low life Gorky wrote a large number of other plays, most of which, reflecting his own rise from itinerant tramp-like poet to a lionised writer, depict a far more elevated social milieu - the world of intellectuals and the middle classes. That is the reason why these later plays of Gorky's have to withstand, and suffer from, comparison with Chekhov. Enemies, written immediately after the Revolution of 1905, suppressed at the time, first performed by Piscator in the Berlin of the early twenties, and in Soviet Russia not until the thirties, is a case in point. The setting is that of The Cherry Orchard and even some characters (the hopelessly unpractical liberal actress; the idle, weak Gaev-like younger brother of the head of the household, who drowns his sorrow at being totally ineffectual in endless glasses of vodka) seem to come straight out of Chekhov's play. The difference is that this family has done what Mme Ranyevskaya failed to do. They have not only gone into business but have a flourishing textile factory next to their country seat and garden. |

|

The first act of Enemies is a masterly piece of construction: the conflict is set between the two partners who own the factory: Skrobotov, the ruthless go-getter and reactionary, and Bardin, the gentle liberal. Skrobotov has been away on leave; in his absence the liberal partner's attempts to curry favour with the workers have undermined discipline. Now they demand the dismissal of a brutal and hated foreman. The liberal boss is inclined to comply with the workers' demand, the ruthless manager wants to close the factory and have a lockout to re-establish complete discipline. After some heart-searchings the liberal boss agrees that the factory should be closed. Everything seems settled, the hard manager goes off to implement the decision - the garden, after breakfast, relapses into Chekhov-like melancholy calm. Suddenly the news is brought that the manager has been shot in a scuffle with one of the workers. He is brought in and dies.

This is strong, splendid theatre, full of suspense, sudden reversals of fortune and the exposition of a number of fascinating characters.

The trouble with the play, however, is that after this initial explosion, neither the author nor the characters quite know how to develop the situation. The murderer must be found and punished and the family must adjust itself to the new situation. But in 1906, when the play was written, one could not yet indicate the final downfall of the Czarist regime or the factory-owning middle-class; so everything had to remain suspended in mid-air. To find enough action to keep another two acts going Gorky had to introduce the unlikely and unsatisfactory self-sacrifice of a young worker who gives himself up as the murderer to protect the real culprit (who has a family and is more valuable to the socialist cause). In a similar vein Gorky presents the crisis in the marriage of the Gaev-like drunkard and his actress wife which ends, Ivanov-like, with the gentleman's exit carrying a revolver clearly intended for suicide; an attempt by that self-same actress to save the Bolshevik who is the leader of the revolutionaries in the factory by offering herself to the public prosecutor; and an outburst of liberal indignation by the teen-age young lady of the family who is a revolutionary, but also a pretty insufferable, intense bluestocking of a bespectacled girl. And of course the Czarist police is suitably brutal and ox-like.

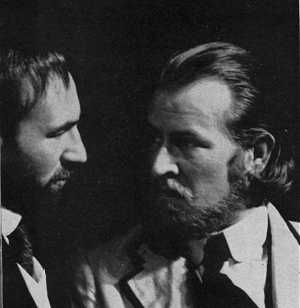

All this becomes, however, charged with a second layer of meaning and irony sixty-five years after it was written: for now we know that while workers got their way with the factory owners through a strike in 1906, they are banned from striking after the Revolution; and we can see that the Czarist police were veritable little gentlemen compared with the Secret Policemen of the Stalinist era (who incidentally murdered Gorky himself, if we are to believe the official version of Gorky's death as it was revealed at the Moscow trials). Is it to bring out this irony that David Jones, who directs the RSC's performance with a brilliant grasp of naturalistic technique, has put Patrick Stewart, who plays the ruthless manager, into a make-up which produces the spitting image of Lenin himself, while Ben Kingsley, who gives a fine portrait of the professional underground revolutionary, appears with the face of Stalin?

Was the intention to show that the ruthlessness of the factory tyrant who exacts an iron discipline is in fact the same as that of the Communist dictator who uses his brutal power to exact the maximum of production from his working class? Be that as it may, Patrick Stewart gives a performance of brilliant drive, hysteria and brutality, all springing from a deep undercurrent of fear and insecurity. Another outstanding performance, in an evening of well-nigh perfect acting all round, comes from John Wood as the weakling brother: he never overdoes the drunkeness and indeed shows a man who drinks immoderately because alcohol fails to dim his lucid, rational awareness of his own ineffectuality and worthlessness. A truly brilliant debut with the RSC company! Alan Howard is as good as always in the unsympathetic part of the dry-as-dust prosecutor; Philip Locke is suitably distraught as the liberal factory owner; and Barry Stanton makes a fine figure of a fat, stupid police-officer.

|

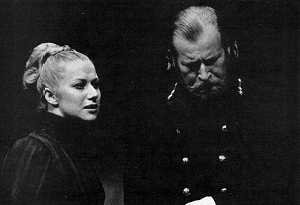

On the distaff side Sara Kestelman is the murdered manager's vengeful wife, Brenda Bruce, the latter-day Ranyevskaya, and Helen Mirren the actress who still loves her drunken husband while already falling for the revolutionary leader. All these are excellent. Mary Rutherford has the most difficult female part in the play: the bluestocking teenager who becomes the spokesman for the author. I am in two minds about this performance. On the surface it is brilliant: this girl has all the intensity of the frustrated spinster-to-be which is already present in the bespectacles young girl: the shrillness, the childishness and petulance, the mixture of naivety and intellectual sharpness are all here. And yet - and that is where my hesitation comes in - all this makes the girl, who surely is meant to be sympathetic, well-nigh unbearable as a human being; one recognises the portrait as a true likeness, but a likeness of a character who is bound to get on one's nerves and prejudice one against any ideas such a person might advocate. Was this too another intentional irony of the producer's? I wonder. |

|

The English version, by Kitty Hunter-Blair and Jeremy Brooks, is colloquial and clear. To sum up: a fascinatingly interesting, if far from perfect, play in a finely acted ensemble performance in an outstanding production by David Jones.