Oedipus in Plaster!

|

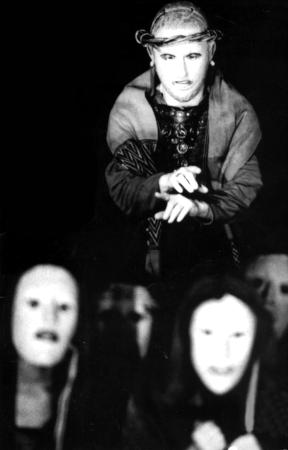

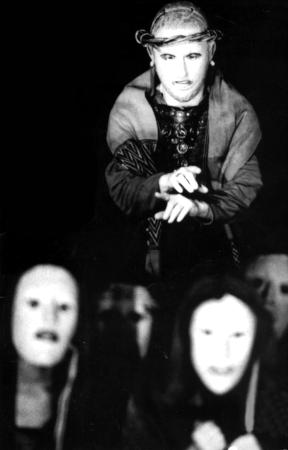

"........The main feature of Fotopoulos's

design, the long narrow tongue-like ramp stretching from the rear of the skene

to a mid-point in the orchestra, was raked from a height of twelve feet, down

to about three feet above the ground. A slightly raised lip, intended to warn

the actors that they were at the edge, ran the length of the ramp on both

sides. But in Oedipus the King a dark red carpet covered the whole ramp

including the raised edges. Entry onto the ramp was via a narrow vertiginous

set of steps leading from a concealed space under the ramp through an opening

cut into the floor. Entrances from it looked spectacular, but were risky for

the actors because of the height above ground, the narrowness of the ramp, and

the fact that they had to negotiate it in masks (some of which were also

covered with a veil) under the glare of powerful lights.....................Not

only was the ramp itself potentially dangerous, but the treads of the steps

leading to it were narrow, and, the first time the stairs were used, there was

no hand-rail. Getting up the stairs in masks wearing ankle-length costumes was

tricky, getting down after returning up the ramp from the bright lights focused

down-stage, felt hazardous. Nor were there any protective rails around the

opening in the floor, and Alan Howard, who used this entrance and exit the

most, had to feel for the first step with his heel, and rely on a stage manager

to come up, grasp his hand, and lead him down safely.......Fortunately the moon

was full during the rehearsals* and at the subsequent performances and by its

light all the actors successfully negotiated their entrances and

exits. |

|

|

Photograph © Allan

Titmuss |

The light of the moon could do nothing to prevent

what happened next. Two-thirds of the way through the dress rehearsal of

Oedipus the King, as Oedipus and Jocasta awaited the arrival of the old

shepherd bringing his terrible news, Alan Howard made a move back up the ramp,

lost his bearings, failed to feel the edge of the ramp, and fell backwards onto

the floor of the orchestra. He hit the ground hard and lay still. There was a

gasp from the spectators, and a scream from Suzanne Bertish (Jocasta), as

people from the audience, actors, and stage-managers, surrounded the fallen

actor. His mask was removed, and for a few terrible seconds, no one knew if

this were to be a real tragedy, and whether Alan Howard were dead or

alive.

After a few minutes he was helped to his feet and

taken to a local hospital where an x-ray revealed that he had sustained a

compound fracture to his right wrist. His arm was set in plaster from the

knuckles to the elbow. He was lucky: it could so easily have been his back or

neck that was broken. Understandably groggy, he returned after his treatment to

sit outside his dressing room, habitual cigarette clamped between his

lips...........................although the company pressed on with work on

Oedipus at Colonus, the stuffing had been knocked out of all of

them...........the understudies, although cast, had not had a single

opportunity to rehearse. If Alan Howard were unable to perform the following

night, the opening performance would have had to have been cancelled. As the

actors left the site in the early morning, the prospects of any further

performances looked very slim. On the one hand there was the threat from Peter

Hall to cancel the production if permission for the fires to be lit** was not

forthcoming, and on the other, the leading actor was now in obvious pain and

discomfort.

Later in the day, after a few hours' sleep, the

company waited anxiously for news in their hotels.............In the afternoon,

following a lunch-time discussion with Peter Hall, Alan Howard decided that he

was prepared to perform that night. It was a characteristically brave decision.

However, there was still no news about the fires. It was decided to take the

risk that the show would go ahead ......

Because, following the accident, the dress rehearsal

of both plays was incomplete (the lighting and sound cues had yet to be

finalised) Hall had decided that the performance, if it were to go ahead that

night, would be a dress rehearsal. If technical adjustments were needed, the

action would be temporarily halted. Before it commenced, Hall informed the

audience of approximately three thousand people of the change in status of the

performance, and the reasons for it...........As the actors put on their

costumes, news came through that the Greek minister had, at the very last

minute, intervened, and the fires could be lit..........

Peter Hall did not stop the performance, and ,

judging by the reception given to it by the audience, it was the right

decision. The level of sustained applause that greeted the actors at the end of

Oedipus at Colonus that night and on the following one, when almost ten

thousand people saw the performance, rang out in the still

night....."

* Technical rehearsals had to be held at

night because of the need to use lighting, avoid tourists and the heat of the

day.

** The production used "flaming braziers"

around the perimeter of the staging. These used real fire. During rehearsal at

Epidauros, when they were lit, word was passed to the Greek archaeological

society who were responsible for all the ancient sites in Greece. They

immediately took action to remind the company that the use of real fire was

forbidden in the theatre at Epidauros - Peter Hall was threatened with a night

in gaol if he lit them! Permission had been asked for, and given, for real fire

to be used, and Peter Hall stated that unlessthe prohibition was rescinded in

time for Friday night's scheduled opening performance he would cancel the

production and the company would return home.

Taken from, Unmasking Oedipus, by Peter

Reynolds.

Published by Royal National Theatre Publications

and NT Education. 1996.